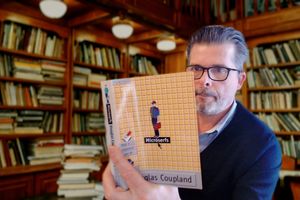

Well, Douglas Coupland's Microserfs — it's a groundbreaking novel about a particular period in time, but it's kinda disappeared into history. So, what's it like reading it today?

Beginning at Chapter 1:

FRIDAY, Early Fall, 1993

This morning, just after 11:00, Michael locked himself in his office and he won't come out.

Stop it, Douglas Coupland, just stop it.

Getting us hooked in just one sentence. Stop it, now.

Bill (Bill!) sent Michael this totally wicked flame-mail from hell on the email system — and he just wailed on a chunk of code Michael had written.

Oh, come on. You're referencing Bill Gates? That Bill? So you're setting this in the real world? With actual people in reality as people in the novel?

We figured it must have been a random quality check to keep the troops in line. Bill's so smart.

Bill is wise.

Bill is kind.

Bill is benevolent.

Bill, Be My Friend … Please!

Actual Mr B. Gates? Come on now.

Microserfs is written as a diary by Daniel, a software tester at Microsoft (yes, that's right — actual Microsoft!), ‘to try to see the patterns in my life’ (pg. 4). So this book is not just a roman à clef, with fictitious names swapped for real people and places — you're going ahead and naming actual them and putting them in your actual novel, Mr Coupland? Come on now.

Microserfs is about the search for meaning, about yearning for purpose in a world becoming saturated with technology. Programmers, coders, testers — they've got hip jobs and eye-watering pay at one of the biggest names in tech, but Daniel and his friends are rapidly heading nowhere however hard they work. Bored and desperately frustrated, something's got to give.

Don't believe me? Well, turn to page 15 (Sunday) — not even out of the first chapter.

We design business spreadsheets, paint programs, and word processing equipment. So that tells you where we're at as a species. What is the search for the next great compelling application but a search for the human identity?

And then, further down the page:

Actually, I've been thinking about this death denial business quite a bit recently. September always makes me think of Jed.

…

I'd like to hope Jed is happy in the afterworld, but because I was raised without any beliefs, I have no picture of an afterworld for myself.

…

Over the last few weeks I've been oh-so-casually asking the people I know about their own pictures of the afterworld. I can't simply come right out and ask directly because, as I say, you just don't discuss death at Microsoft.

Coming out with the big ones, already — identity, death, and what's beyond it. Douglas, come on — really? Who's Jed? — that's Dan's little brother, who died aged 12, a boating accident.

Soon, things compound and Dan finds himself with lots of big thoughts.

- The 20-somethings, he realises, are ‘the first Microsoft generation’ (pg. 16) who've only known a world with the company's products in it.

- On Monday, Dan's dad gets fired from his long-standing job at IBM (pg. 21) — his father had been expecting a promotion.

- Dan and his friends begin to talk about the fragility of the workplace, about people in their 50s being ‘dumped out the economy’ (pg. 23).

- They reflect on the changes of the '90s, a decade without an architectural legacy, though maybe, they think, ‘code is the architecture of the '90s.’

- Dan realises the routine blandness of his life — eating the same thing every day, little difference between workdays and other days, never going to the movies, gripped only by WinQuote, his stock-value checker.

Dan does little to change anything.

Michael, the flame-mail-from-Bill guy, the self-recriminating hermit of the first sentence, gets sent to California, while the others stay at MS HQ in Redmond, Washington. Later, Michael sends his old friends an email — he's created a computer game, 'Oop!', has taken on Dan's as his first employee and wants the others to join too.

Through resentment and frustration, Daniel and his friends — all except Abe — move away in turn from being Micro-serfs, as they call themselves, to join Michael in his new venture in their search to grow and become more fulfilled, creating technical things as an expression of themselves.

Abe ends up saving Oop! by investing in the company.

Through Dan's stream-of-consciousness journal we follow the fragile lives of this group of geeks. We find them vulnerable and tender, and Coupland portrays them against-type of the digital nerd cliché.

Dan falls in love with Karla. He confronts his past, particularly his brother's death, his father's redundancy, and his mother's failing health.

It’s late and Karla’s asleep and blue by the light of the PowerBook.

I’m thinking of her as I input these words, my poor little girl who grew up in a small town with a family that did nothing to encourage her to use her miraculous brain, that thwarted her attempts at intelligence—this frail thing who reached out to the world in the only way she knew, through numbers and lines of code in the hope that from there she would find sensation and expression. I felt this jolt of energy and this sense of honor to be allowed entrance into her world—to be with a soul so hungry and powerful and needful to go forth into the universe.

pg. 101

Dan's mother becomes a surrogate mother to the Oop! squad. She suffers a stroke, and rather than recoiling Dan's friends all gather round, even offering a computer as a means to communicate (pgs. 366–69).

Coupland's book, published in 1995, is a powerful prefiguring of the future we're living in.

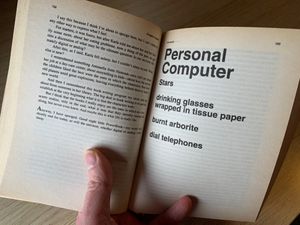

Dan's journal is written on an Apple PowerBook, and a Coupland uses this to play with the form and style of the novel. In doing so, Coupland pre-empts the blog format that emerged a decade later.

Oop! itself is one of the most powerful. With Oop! (a reference to object-oriented programming, which became the mainstay paradigm of software engineering in the 1990s), Coupland encapsulates the venture-capital backed tech start-ups that dominated the digital world from their heartland in Silicon Valley and gave rise to the dot-com bubble that burst so dramatically in slow motion in the late-nineties and early-noughties.

The book is full, also of coded messages.

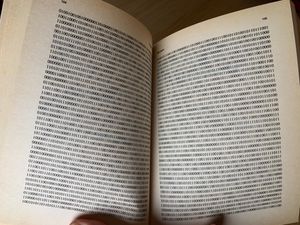

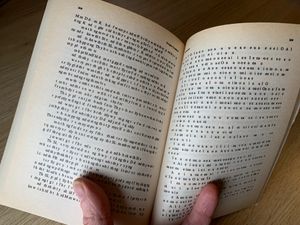

Pages 104-05 are entirely in binary. When decoded, it's a version of the Rifleman's Creed adapted for the age of programmers and geeks.

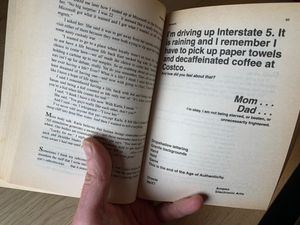

On pages 308–09, there's text from a message sent by Patty Hearst, daughter of newspaper magnate Randolph Hearst, to her parents when she was kidnapped by a far-left militia … except the constants are on the left page, the vowels on the right — “Mom, Dad, I'm okay …” it begins.

This is a superb novel, one to fall in love with. Coupland paints a world of transcendent geek culture, but more than that of a place in which obsessive and complicated people move forward to find harmony, with themselves, with their tribe, with the world beyond.

But read it also to feel the pulse of its prescience — as we sit on the precipice of an AI bubble about to burst, Coupland's premonition of the hedonism and money-driven irrationality of the dot-com era is still powerfully relevant today.

Get hold of Douglas Coupland's Microserfs for yourself — it's a truly excellent novel.

And if you like this book, you may also like JPod — his follow-up for the Google generation.